BUDDISM

just as water flows in the streams and rivers and fills the Ocean, may all your moments of goodness touch and benefit all beings, for those who are here now and those have gone before. May all your wishes be soon fulfilled as completely as the moon on a full-moon night, as successfully as from the Wish-Fulfilling Gem. May all dangers be averted; may all disease leave you. May no obstacles come across your way and may you enjoy happiness and long life. May those who are always respectful, honoring the way of the elders, prosper in the four blessings of long life, beauty, happiness, and strength.

INTRO TO BUDDHISM

BUDDHISM. The religion of about one eighth of the world’s people, Buddhism is the name for a complex system of beliefs developed around the teachings of a single man. The Buddha, whose name was Siddhartha Gautama, lived 2,500 years ago in India. There are now dozens of different schools of Buddhist philosophy throughout Asia. These schools, or sects, have different writings and languages and have grown up in different cultures. There is no one single “Bible” of Buddhism, but all Buddhists share some basic beliefs.Buddhism is a Western word. The religion is known in the East as the Buddha-Dharma, or the teachings of the Buddha. These teachings, based on his personal experience of Enlightenment, or Awakening, form the foundation of Buddhism. For every Buddhist the religion is both a discipline and a body of beliefs: that is, Buddhists share beliefs about the nature of the world and how to act within it.

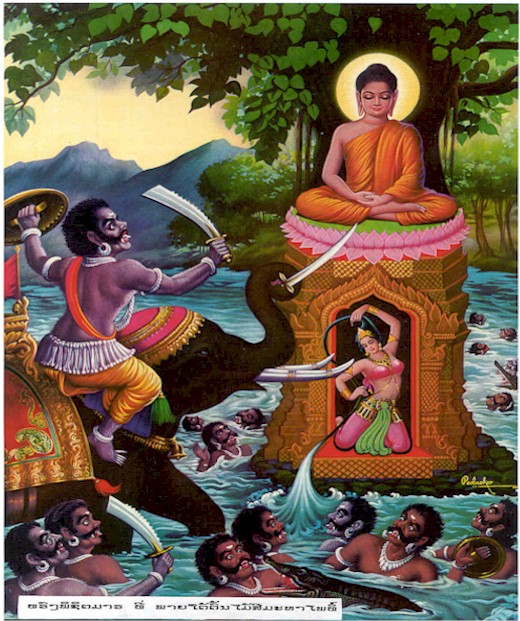

Budh in the Indian Sanskrit language means “to wake up, to know.” Buddha means “the Awakened or Enlightened One,” and all Buddhist teachings try to share the Buddha’s experience of awakening to truth. Having led an indulgent life as a young man, Siddhartha Gautama decided to pursue a course of bitter self-denial. Yet he felt that this brought him no closer to the truth he sought than the rich life he had led. One day he felt close to reaching his truth, and he sat down under a tree now known as the Bo tree (short for Bodhi, or “enlightenment”).

There he attained the bliss and knowledge he had been seeking. Legend has it that, though tempted by evil demons, he sat quietly under the tree for 49 days. This became known as the Immovable Spot. He devoted the rest of his many years, until his death at the age of 80, to wandering through India teaching the people

The Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path

Although he could have chosen to sit happily under a tree forever, the Buddha wanted to make his inspiration about the nature of life available to others for their betterment. He worked his experience into a doctrine known as the Four Noble Truths, and these truths are the basis of all schools of Buddhism.

The first truth is that all life is suffering, pain, and misery, or dukkha. The second truth is that this suffering has a cause–tanha, or selfish craving and personal desire. The third is that this selfish craving can be overcome. The fourth truth is that the way to overcome this misery is through the Eightfold Path.

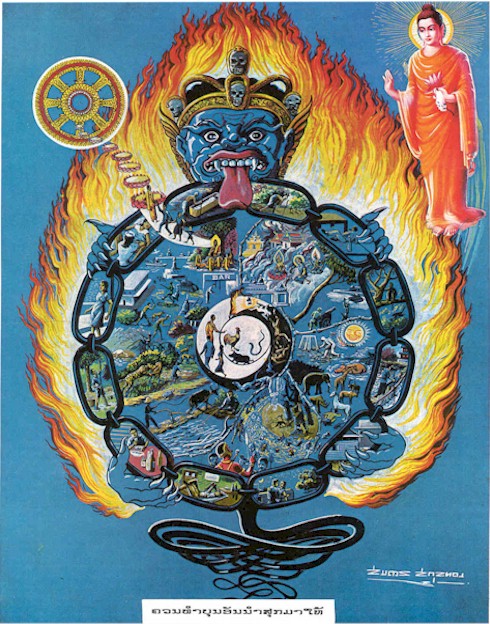

Buddhists all believe in the idea of “no-self,” that people make a mistake when they identify too strongly with their own personal existence in any one life. To the follower of the Buddha, life goes on and on in many reincarnations or rebirths. This wheel of rebirth, known as samsara, condemns the individual to the suffering of being alive and striving. Life’s goal, according to the Buddha, is to escape from this cycle of rebirth, to stop being born as a suffering individual with selfish cravings and passions.

This release is called Nirvana, the highest bliss, the end of the self. It was this bliss that the Buddha felt under the Bo tree. The way to achieve Nirvana is to follow the steps of the Eightfold Path. The Buddha called his path the Middle Way, because it lies between a life of luxury and a life of unnecessary poverty. Not everyone can reach the goal of Nirvana, but every practicing Buddhist is at least on the Path toward Enlightenment.

A basic step, too basic to be listed as one of the eight, is Right Association. One cannot achieve perfection unless one keeps the right company. A Buddhist is supposed to associate with other seekers of truth in a spirit of love.

1. Right Knowledge is knowledge of what life is all about; knowledge of the Four Noble Truths is basic to any further growth as a Buddhist.

2. Right Aspiration means a clear devotion to being on the Path toward Enlightenment.

3. Right Speech involves both clarity of what is said (taking care to say just what is meant) and speaking kindly and without malice.

4. Right Behavior involves reflecting on one’s behavior and the reasons for it. It also involves five basic laws of behavior for Buddhists: not to kill, steal, lie, drink intoxicants, or commit sexual offenses.

5. Right Livelihood involves choosing an occupation that keeps an individual on the Path; that is, a path that promotes life and well-being, rather than the accumulation of a lot of money.

6. Right Effort means training the will and curbing selfish passions and wants. It also means placing oneself along the Path toward Enlightenment.

7. Right Mindfulness implies continuing self-examination and awareness. The ‘Dhammapada’, a basic Buddhist text, begins, “All we are is the result of what we have thought.”

8. Right Concentration is the final goal–to be absorbed into a state of Nirvana.

Buddhists believe that the first two steps on the Path can be taken by anyone. The third, fourth, and fifth are for novice monks, and the last three steps show real progress toward the goal. As in so many Eastern traditions, the religion is not based on attaining the goal so much as being on the road

Thus Have I Heard

The Buddha lived and taught for almost 50 years after his Enlightenment, but he did not write a single word of his teachings. No one during his lifetime put anything he said in writing. His original teachings were handed down from one generation to the next by word of mouth. This continuing oral tradition was not put in writing until about three centuries after his death. By this time, the religion had split into a number of schools. Each school set down the teachings as it understood them.

Since the Buddha felt his teachings were for everyone, not just scholars, he spoke in a language many people in India understood, Pli. (Hindu texts were written in Sanskrit, which few people could read or understand.) This was a revolution on a scale of the Roman Catholic mass being said in the local language instead of in Latin. In a country with a social caste system of segregation, the Buddha’s democratic views were a novelty and won him many followers.

Since no one wrote down exactly what the Buddha said, all the Buddhist teachings begin with the phrase, “Thus have I heard.” Then they go on to tell what Buddha taught and believed. The oldest Buddhist writings, the Pli Canon, are also known as the Three Baskets. One of the baskets, the ‘Vinaya’ (meaning “discipline”) spelled out the rules for the Buddhist monks. These monks, the community known as the Sangha, constitute the oldest continuous religious order of all the world’s great religions

The Lesser Vehicle and the Greater Vehicle

After the Buddha’s death, his followers split into a number of factions, each with its own interpretations of the master’s teachings. Within 200 years two major traditions emerged. This schism has persisted to the present time. Even within the major traditions, there are smaller sects.

The older tradition, known as the Way of the Elders, is also called Hinayana, or the Lesser Vehicle. Its adherents are the more conservative interpreters of the Buddhist teachings, and the name was given them by the more liberal sect, who call themselves the Mahayana, or the Greater Vehicle. A more respectful name for the Way of the Elders is Theravada Buddhism. It is still the main tradition in such countries as Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia.

The word vehicle suggests that Buddhism is a means of journeying from the pain of this world to the bliss of the next. Each tradition believes that it is the best vehicle for Buddhists on their Path. The Greater Vehicle, Mahayana, is the form of Buddhism popular in Mongolia, Tibet, China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and Nepal. Zen Buddhism is a derivative of the Mahayana school, which has far more followers than the Theravada school. The Mahayana Buddhists were able to spread and make more converts because they chose to interpret the teachings of the Buddha more liberally than did the Theravada Buddhists. For example, the ‘Vinaya’ states that monks can only wear cotton robes, which would be fine in India. But when monks wanted to carry the message north to colder climates, they were deterred by their light clothing. Mahayana monks chose to wear wool and felt robes in order to bring Buddhism to the Mongols and into China. They were more flexible than the Theravada Buddhists.

However, the basic difference between the two schools is in how they see the life and teachings of the Buddha. Theravada Buddhists see him as a man, a saint, who chose to give up all his wealth and comfort to achieve Nirvana. Mahayana Buddhists, on the other hand, stress the Buddha as a savior who devoted his life to serving and teaching others. He did not choose to rest, content in his own Enlightenment.

This difference of interpretation led to the fundamental split between the two schools. Theravada Buddhists concentrate on the emancipation of the individual through his own efforts, while the Mahayana stress salvation through a life of good works.

Since all the teachings of the Buddha were written long after his death, each school disputes the other’s writings. The Theravada school criticizes the writings of the Mahayana for not being authentic. The Mahayanas write that the Buddha taught each according to his own level of understanding and taught only the most basic ideas to the Theravadas. His deepest insights, say the Mahayanas, he reserved for those on the Greater Vehicle (the Mahayanas).

The Three Jewels

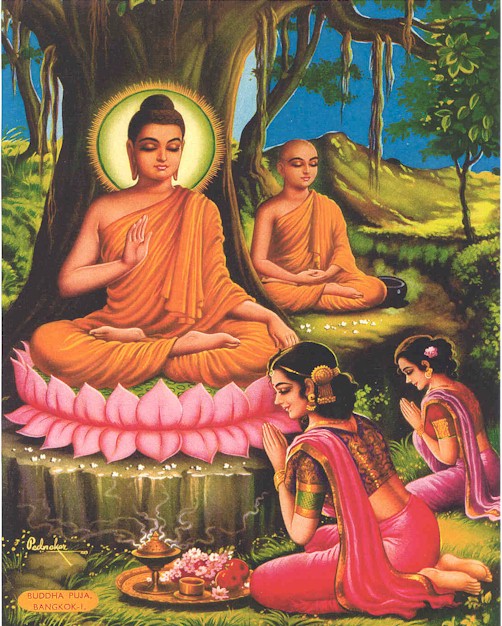

In all its many different forms, Buddhism has three cornerstones that are always the same. These are the Three Jewels: Buddha, the teacher; Dharma, the teachings or laws; and Sangha, the community of believers. Monks and devout laypeople believe that these three elements of their religion shelter and protect them in the world. This is expressed in a Buddhist prayer, “I take refuge in the Buddha. I take refuge in the Dharma. I take refuge in the Sangha.”

For those who choose to live their lives as Buddhist monks (a course open to both men and women), the Three Jewels form the center of their daily lives. Prayer, meditation, and other rituals keep them on the Eightfold Path. In the Theravada tradition monks live isolated lives in their monastery retreats, whereas Mahayana monks include service to the larger community as part of their Path.

Throughout the Buddhist countries of Asia, holidays are celebrated to commemorate the life and teachings of the Buddha. The Theravada tradition celebrates four days every month as uposatha days. These are the new moon, the full moon, and the eighth day after each new and full moon. Sermons, prayers, and offerings mark the uposatha day ceremonies.

Theravada Buddhists continue the practice of vassa, a three-month retreat during the rainy season, from July to October. The Buddha himself made this retreat. Many laypeople take a monk’s vows for three months, and monks mark their years in the community by the number of vassas they have attended.

Three major points in the life of the Buddha are celebrated in all Buddhist countries–his birth, Enlightenment, and his death or final Nirvana.

In countries of the Theravada tradition, all three events are celebrated on the same day. This is the full moon of the sixth lunar month, usually falling in April. In Japan and other Mahayana countries, the Buddha’s birth is remembered on April 8, his Enlightenment on December 8, and his death on February 15.

In China and Japan, with their long traditions of ancestor worship, Buddhists have an All Souls Festival for the dead. This festival has two purposes: to remember the dead and to bring final peace to the spirits of those who have died unburied.

Anyone can step onto the Eightfold Path toward Enlightenment, and millions of laypeople follow Buddhist teachings and rituals to some extent. Those who have devoted their lives to the Path are known as Bodhisattvas, or Buddhas-to-be

The Last Teaching of The Buddha

| Beneath the sala trees at Kusinagara, in his last words to his disciples, the Buddha said, “Make of yourself a light, Rely upon yourself: do not depend upon anyone else. Make my teachings your light. Rely upon them: do not depend upon any other teaching Consider your body: Think of its impurity. Knowing that both its pain and its delight are alike causes of suffering, how can you indulge in its desires? Consider yourSelf; think of it and cherish proud and selfishness, knowing that they must all end in inevitable suffering? Consider all substances; can you find among the many enduring self;? Are they not all aggregates that sooner or later will break apart and be scattered? Do not be confused by the universality of suffering, but follow my teaching, even after my death, and you will be rid of pain. Do this and you will indeed be my disciples “My disciples, the teachings that I have given you are never to be forgotten or abandoned. They are always to be treasured, they are to be thought about, they are to be practiced. if you follow these teachings you will always be happy. |

“The point of the teachings is to control your own mind, Keep your mind from greed, and you will keep your behavior right, your mind pure and your words faithful. By always thinking about the transiency of your life, you will be able to resist greed and anger, and will be able to avoid all evils.

“If you found you mind tempted and so entangled in greed, you must suppress and control the temptation; be the master of you r own mind.

“A man’s mind may make him a Buddha, or it may make him a beast, Misled by error, one becomes a demon; Enlightened, one becomes a Buddha, Therefore, control your mind and do not let it deviated from the right path.

“You should respect each other, follow my teachings, and refrain from disputes; you should not, like water and oil, repel each other, but should, like milk and water mingle together

“Study together, learn together, praxis my teachings together, Do not waste your mind and time idleness and quarreling, Enjoy the blossoms of Enlightenment in their season and harvest the fruit of the right path.

“If you neglect them, it means that you have never really met me, It means that you are far from me, even if you are actually with me; but if you accept and praxes my teachings, then you are very near to me, even though you are far away.

“Disciples, my end is approaching, our parting is near, but do not lament, Life is ever changing; none can escape the dissolution of the body, This I am now to show by my own death, my body falling apart like a dilapidated cart.

“Do not vainly lament, but realize that nothing is permanent and learn from it the emptiness of human life, Do not cherish the unworthy desire that the changeable might become unchanging, “The demon of worldly desires is always seeking chances to deceive the mind, If a viper lives in your room and you wish to have a peaceful sleep, you must first chase it out.

“My disciples, my last moment has come, but do not forget that death is only the end of the physical body, The body was born from parents and was nourished by food; just as inevitable are sickness and death, “But the true Buddha is not a human body:- It is Enlightenment, A human body must die, but the Wisdom of Enlightenment will exist forever in the truth of the Dharma, and in the practice of the Dharma, He who sees merely my body does not truly see me. Only he who accepts my teaching truly sees me.

“After my death, the Dharma shall be your teacher. Follow the Dharma and you’ll be true to me “During the last forty-five years of my life, I have withheld nothing from my teachings. There is no secret teaching, no hidden meaning; everything has been taught openly and clearly. My dear disciples. This is the End, In a moment, I shall be passing into Nirvana. This is my Instruction.

The Spread of Buddhism

The Spread of Buddhism

In India for the first 200 years after the Buddha’s death, Buddhism was a local religion. When King Asoka converted to Buddhism in the 3rd century BC, he used the resources to spread the religion as far south as Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka) and as far north as Kashmir. Buddhism has been moving, growing, and changing ever since.

Beginning about AD 150, trade between India, China, and the Roman Empire brought Indian people and ideas into China. Buddhism traveled overland from India to China as Mahayana monks rode with the traders’ caravans. In the 3rd century the Mahayana sutras, key texts on the teachings of the Buddha, were translated into Chinese. In the 4th and 5th centuries, Buddhism became the dominant faith of China, which reached a peak in the 7th century.

It was in the 4th century that the religion was introduced into Korea. First accepted by the royal court, the religion slowly spread among the Korean people. Ultimately one sect of Chinese Buddhism, known as Ch’an (Zen in Japanese), became the dominant school of Buddhist thought in Korea.

From Korea Buddhism was brought to Japan for the first time in the 6th century, between 550 and 600. Korean royalty sent missionaries to the Japanese imperial court, assuring the Japanese that Buddhism would bring great blessings to their country. In the 7th century, a devout Buddhist regent, Prince Shotoku, introduced Buddhism into the governing of the state. By the 8th century, Buddhist monks were working as civil servants for the imperial government in the outlying areas. After the 8th century, many different sects grew up and prospered. Those with the biggest following were known as Tendai and Shingon. Shingon now claims more than 15 million followers. The largest sect in Japan today is known as the True Pure Land Sect, or Jodoshinsu.

The Chinese Ch’an group, which flourished in China between the 11th and 13th centuries, was the last great Buddhist sect to thrive in China. It was introduced into Japan as Zen in the 9th century, but really became popular around 1200. During Japan’s civil war (1300 to 1600), the Zen temples were the only available centers of peace and learning. Buddhism was introduced into Tibet in the 7th century. Tibetan Buddhism is a combination of Mahayana and Vajrayana elements from northern India.

By 1200 a Muslim dynasty had come to power in India, and Buddhism virtually disappeared from the land of its origin. Many Buddhist elements still survive in Indian Hinduism, however.

Modern Buddhism in the East

Buddhism has always been ready and able to develop in new environments, with different cultures and customs, and yet still remain faithful to the teachings of the Buddha. It is therefore not surprising that Buddhism continues to flourish in the East.

During the colonial expansion of the European powers throughout Asia, only Japan and Thailand were not colonized. In all other Buddhist countries, Buddhists chose to take a nationalist and political stand against imperialism. As one example, the king of Burma proclaimed himself the protector of the Buddhist community in order to protect his people.

In the 20th century Buddhism has had to contend with Communism, with varying degrees of success. Mongolia, China, Tibet, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam had all become Communist countries by the late 1970s, though most of them later rejected Communism. The most damage to Buddhism was done in Tibet, where the Chinese Communist occupation that began in the 1950s almost wiped out the spiritual and cultural basis of the Tibetan culture. In 1959 the Dalai Lama, head of the Tibetan Buddhist hierarchy, fled to India with 70,000 followers. In his absence thousands of temples were destroyed and monks were persecuted. Many monks went to Europe or the United States.

In Japan, the most industrialized of Far Eastern nations, Buddhism is still a strong force. New sects are developing. One, Soka Gakkai, is based on the 13th-century teachings of Nichiren. Today Soka Gakkai claims more than 10 million followers and is a minor force in Japanese politics. This sect is actively soliciting new members in Japan and in the West.

Buddhism in the West

Western thinkers have been interested in Buddhism for nearly 200 years, from the time of German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer. European artists, scholars, and philosophers started Buddhist study groups in Europe early in the 19th century.

Buddhism traveled to the Canada and United States with 19th-century immigrants. Many Buddhists arriving from Asia established communities and temples to continue their religious practices. At first, the largest communities were on the West coast, where the immigrants arrived. Now there are Buddhist communities throughout the United States. Many different schools of Buddhism are represented, the two fastest growing being Zen and Tibetan Buddhism.

Many Westerners have become so deeply interested in Buddhism that they are becoming Buddhist teachers themselves. In the United States the centuries-old religion is undergoing yet another major transformation. Much as it has been adapted before to so many cultures, Buddhism is being modified to fit 20th-century American ideas and culture.

The Buddha himself seemed to know that Buddhism would never die if it maintained this pattern of new growth. When someone asked him how a drop of water could be prevented from ever drying up, he answered, “by throwing it into the sea.”